|

|

|---|---|

|

|

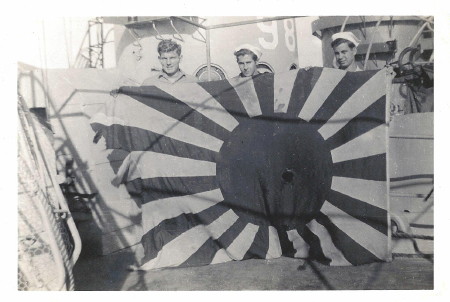

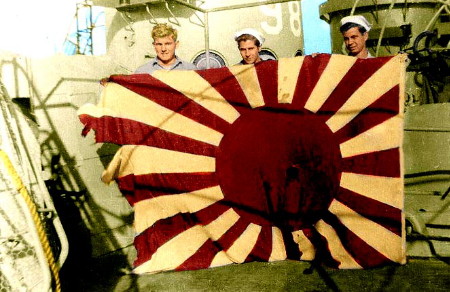

LCI 982 Story

The Japanese Flag pictured was donated to the AFMM in memory of Richard H. Adair Jr. of LCI 982.

Thanks to Ken and Tom Adair!

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

LCI 982

United States Ship

U.S.S. LCI(L)-982

LCI (L) -982; dp. 209; l. 159’; b. 23’8”; dr. 5’8”; s. 14.4 k.; cpl. 40; a. 5 20mm.; cl.

LCI(L) – 351)

LCI(L) - 982 was laid down 23 March 1944 by Consolidated Steel Corp., Orange, Texas; launched 18 April 1944 and commissioned 16 May 1944, Lt. (j.g.) L.R. Dawson in command.

After conducting landing exercises and other aspects of her shakedown, LCI(L) - 982 departed Galveston, Texas on 10 June 1944, enroute to the southwest Pacific war zone. Transiting the Panama Canal 19 June she sailed the southern route to the Admiralty Islands arriving Manus early in August. For six weeks she supported operations at Humboldt and Maffin Bays, New Guinea prior to steaming 16 October for the Leyte, Philippines invasion scene.

From this base she embarked elements of the 503rd Parachute Reg., 24th Infantry who first stepped ashore at Mindorok, 15 December. Early in January 1945 her LCI(L) Group 45 loaded rangers of the 6th Battalion who landed 10 January via Army DUKS on Blue Beach, Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, where high surf proved more of an obstacle than the Japanese. Employed on inter-Philippine island logistic missions until the end of the war, LCI(L) Group 45 then came under control of Commander, Vangtze Patrol. Sailing via Okinawa, she arrived at Shanghai early in October but on the 10th was redirected to Ningpoo. Here troops of the 70th Chinese Army boarded and 2 days later debarked to complete the occupation of Formosa.

Not involved in further troop movements, she departed the China coast 1 December. Again transiting the Panama Canal LCI(L) - 982 reported at Green Cove Springs, Florida, on 20 May 1946 and decommissioned 24 June joining the 16th Reserve Fleet.

Reclassified first in 1949 as LSIL – 982, the Korean conflict brought conversion at Charleston, S.C. to an AMCU and a recommissioning 19 December 1953. Owl (AMCU – 35) departed January 1954 for the 15th Naval District arriving Balboa, Panama Canal Zone 5 February. Besides serving as a mine hunting harbor defense ship she conducted a 2 week Reserve Training cruise to Cartagena, Colombia in December 1954. Reclassified MHC – 35 on 7 February 1955, her basic duties remained the same until 2 August 1957 when she departed the Naval Station Rodman, C.Z. for Boston and retirement. Owl (MHC – 35) decommissioned for the last time 1 November 1957 and was struck from the list of Naval Vessels 17 October 1957.

As LCI(L) – 982 she received 2 battle stars for World War II service.

Travels of the LCI-982

Being an account of what one sailor saw and photographed – during the great war in the Pacific

By Frank Nemetz, Sr.

Photography by the author

After attending various navy schools at several different bases around the country, I was finally sent to Solomon’s Island, Maryland, in early 1944 where I and my future shipmates were assembled as a crew. Informed that we were to man a brand new LCI, our three officers and 25 enlisted men were then sent south via rail to Texas.

We were a mixed group of men coming from all walks of life but our geographic origins were principally from the South, East and Midwest. A few days after our arrival in Orange, Texas, we were assigned our new ship, the LCI(L) 982 build by Consolidated Shipyards. Commissioning of the ship was followed by outfitting and shakedown cruises in the Gulf of Mexico. The water in the Gulf can be rough and for many of the crew, it was their first voyage over saltwater. The crew affectionately named the ship “The Pitching Bitch.” The feeling was that, due to our rather flat bottom, the ship could roll and pitch even in dry dock.

The humorous remarks and misnomers continued; “Long Crude Interior.’ “Ambiguous Farces,” “Shoe Clerks,” “The ship was expendable and would not return to the States.” The officers and men quickly developed a sense of respect and loyalty to the “982,” as she was most often called, just as all Navy men did towards their ships they were assigned to.

With out short shakedown period completed, we were given a full supply of provisions, fuel, water, and one more officer and on 10 June 1944 we headed for the Canal Zone. We reached Coco Solo on 17 June, proceeded through the Panama Canal and arrived at Balboa where the crew was allowed to pay its traditional respects in Panama City.

The 982 then sailed for the Island of Bora Bora, one of the Society Islands, embarkation day being 21 June. Nineteen days later the crew lined the rail to watch a large volcanic mountain protrude over the horizon. The trip was, for the most part, a boring one, although we were constantly entertained by thousands of flying fish as well as dolphins which would race and dart around the ship, all seeming to have great fun. Upon arrival, we dropped anchor for three days and were resupplied by “bumboats.” Leaving Bora Bora on the 10th, our next destination was Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides. Training and drills were continued daily to better prepare us for things to come. Eleven days out we arrived at our destination where we once again went through the resupply routine. Departure day this time was 29 July as the skipper pointed the 982’s bow for Manus Island in the Admiralties group. En route, TBF Avengers appeared and proceeded to make practice torpedo runs at us. Scuttlebutt was that they were from the USS Lunga Point (CVE 94). A few hundred drills later we finally arrived at Lorengau, Manus Island on 5 August 1944. By this time we were all beginning to wonder where we would eventually end up for our first assignment and what our role would be when we reached the fighting zone. While LCIs were designed to deliver troops to the beach in an amphibious landing operation, such operations were relatively few and far between and there was a lot of time left to kill for craft such as ours. It was well known that many an LCI spent the better part of its career acting as a small cargo vessel running around between islands, delivering this, picking of that, and waiting for another invasion. Fortunately, our mystery didn’t last much longer.

Manus has a fine harbor and it was here that the Navy was developing he largest supply and repair facility in the South West Pacific. The harbor was a major staging area and it was here that we were assigned to LCI Flotilla 15 consisting of some 36 ships, all under the command of a Captain Deuterman. We were further divided into three groups of 12 ships each. Our group, 44 was led by Lt. Cmdr. Tucker. A short range radio was soon installed aboard ship for intergroup communications and we were given our first code name “Hillbilly 82.”

Real training was soon underway then the groups participated in mock invasions, beaching, formation cruising, gunnery, all coordinated with radio code or flag hoists.

The Flotilla finally left Manus on 26 August to get another step closer to the war zone. Our group arrived at Lae, New Guinea, on 27 August and then touched at Finschaffen and proceeded up the coast to Hollandia which was then under construction as a large supply base. We soon left where we assembled as a task force and departed for the invasion of Morotai on 11 September 1944. The 982 was used as a spare and did not carry troops. On the first day out of Morotai, we were ordered to return to Hollandia. We could hear Japanese voices talking excitedly on our radio but had no idea what was going on. We anchored in Juatefa Bay, a small inlet that joins Humboldt Bay and sat wondering whether our next mission would be as abortative as our first.

Many ships were arriving and assembling in Humbodt Bay and we all figured that a large scale invasion was imminent. We took on water, fuel and supplies and sat and watched as several hundred ships left the bay on 16 October. Two days later, we found out that we, too, would be on our way to invade the Philippines at Leyte Gulf.

Arrival in Leyte Gulf was 22 October and as we entered the gulf, we were escorted in by the destroyer USS Morris. We continued on into San Pedro Bay for our assigned anchorage. The following morning the war came to us.

It came in form of the Divine Wind. The planes would first drop their bombs on the Tacloban airstrip and then head out to look for ships to Kamikaze. It didn’t take us long to realize they were playing for keeps.

After being hit by any number of shells from different guns on different ships, a Zero crashed into the water about 100 yards from our bow. I remember hoping that would be as close as one would ever get to us. The anti-aircraft fire was devastating. We received orders to lay smoke and that order became our daily and nightly duty while we were in the bay.

October 24 was a grim day for the small group of vessels in our area. First a tug (of all things!) was hit by a Kamikaze but managed to beach itself on a small isle off Tacloban. Then the LCI(L) 1065, one of our sisters, was hit by one of the suicide pilots and although we were only a short distance away and sped to the scene at flank speed, she had already slipped under by the time we arrived, taking several of her crew with her. Survivors said she sank in less than one minute.

Air raids continued day and night. Enemy planes dropped bombs indiscriminately at night. The incredible heavy AA fire would easily surpass any fireworks show I have ever seen. As we meandered around the larger ships on evening laying smoke, two PT-boats were blown out of the water by what appeared to be direct bomb hits. We were straddled by bombs on several occasions. A few days later, another one of our number, LCI(L) 684 was also hit by a Kamikaze and although the impact blew the stern completely off the ship, she managed to make for a beach and was thus salvaged.

On 31 October, we were ordered to pick up a contingent of Army troops and we headed for the Island of Panaon which is located off the southern tip of Leyte. The troops were discharged the following day on a comfortably dry beach. Shortly after withdrawing from the beach and dropping anchor, an enemy plan dashed low over the hills from the other side of the island and caught us with our pants down. He tried to skip bomb our escort, the destroyer USS Anderson. Although the attempt was unsuccessful, the Anderson was not so lucky a few hours later. Two Japanese aircraft droned into sight high overhead and one suddenly peeled off to make its final dive. We watched in a suspended state of awe as the destroyer fired furiously with everything it had at the oncoming Kamikaze, but to no avail as the plane crashed itself in a great ball of fire on the fantail of the destroyer. As the Anderson limped back to Leyte Gulf, we were left to ponder our fate. Our tiny flotilla returned to Leyte unescorted that night.

We had arrived in Leyte Gulf, “we” being our little flotilla of LCIs, on 22 October, 1944. Two days later we heard about the naval action off the coast of Samar and about the heavy gunfire at the entrance to Surigao Strait. While we were relatively safe in our seclusion with the Gulf - - along with several hundred other ships – we could hear Navy pilots on the radio pleading for places to land due to lack of fuel. One of our carriers, we knew, had been sunk and at least two were damaged. The baby flattops appeared to be taking a pounding. The naval battle of Surigao Strait needs no recounting here, but suffice to say it was clear to us even then that if the Japs managed to break into the ranks of the scores of invasion ships anchored with us, they could have had a field day – at least until Halsey arrived back on the scene. As it turned out, Admiral Oldendorf broke the back of the Imperial Navy. The Japanese planners had hoped to fight the decisive battle, and that is exactly what happened -- but with a different ending.

Our second trip to Panaoa Island was completed and for several days we were involved in “smoking.” Enemy air raids were still prevalent night and day and it seemed to us that to hide the big ships laying smoke would be our eternal lot.

On 24 November we were moored alongside a water ship with the LCI 979 and a PC outboard of us. We finished taking on water and backed out while the LCI 979 and the PC banked into the water ship. We had backed out about 100 yards when I heard gunfire erupt in the distance. CQ was sounded and I ran to my station in time to see a single enemy plane drop a bomb which landed squarely between the LCI 979 and the PC. As the water ship cast off all lines from the stricken craft, small boats were immediately in the water, heading for wounded crewmen who had been blown over the side. We headed back in as well and maneuvered alongside LCI 979. As we tied the two sisters together, we realized how badly the 979 had been damaged by the blast. I, along with Ensign Huffington and four other crewmen went aboard the 979. The Ensign and our pharmacist mate administered first aid to the wounded while I and part of my Black Gang went below. We waded in diesel fuel up to our hips and attempted to plug the shrapnel holes with pillows. We then proceeded to the engine room. Since most of the holes were in the port side, the 979 was developing a list. We began pumping fuel to the starboard side and also over the side. This action pulled most of the holes in her port side out of the water. Meanwhile, the 982 was slowly underway and the two ships headed for the shore. In about one hour we were able to beach the 979 near Tacloban, Leyte, and the little ship was saved.

We had seen the three men who were killed on deck and this included the 979”s commanding officer. In addition, 14 of her crew were wounded along with three dead and 17 wounded on board the PC. Come to find out, even at the distance we were from the explosion, one of our crewmen managed to receive a shrapnel wound as well. The 979 had received about 150 holes in her port side extending from the conning tower to below her waterline. While only a minor skirmish, we all felt at the time as though we had been through a traumatic experience. As the 979 lay stricken on the beach alongside the LCI 684 which had been damaged a few weeks earlier, it gave us all pause to think that we might be next. Three LCIs were lost or put out of action in less than three weeks in Leyte Gulf thanks to two Kamikazes and a bomb and it was very disturbing to see sister ships suffer such fates.

Over the next few days we acted as tender for the LCI 979. Two days after the raid, we watched three separate air raids take place, these being directed mainly at the seaplane tenders that were anchored a few hundred yards from where we were beached. Luckily, none of the bombs found their mark. P-38’s were hot on the tails of the attacking Japanese aircraft and managed to shoot down two of the planes. We watched in bewilderment as an undoubtedly excited Catalina pilot made a landing in the gulf and was approaching his tender when suddenly the big flying boat flipped with her nose under water and sank within a few seconds.

***

We missed out on the Ormoc invasion due to our duties in acting as tender for the 979. A few days later we were relieved as tender and resumed smoking with emphasis on “Smoke Nemo! Smoke Nemo!” (which meant lay smoke for the cruiser Nashville). As we went slowly underway, smoking around the large ships, we were straddled by enemy bombs on several occasions. Shrapnel from friendly AA fire clanged on our decks. The enemy bombing of the Tacloban airfield by night and the anti-shipping Kamikaze raids by day were incessant and went on for many days.

During the first week of December we caught wind of a second invasion being prepared. We were ordered to take on fuel, water and supplies for an extended operation then traveled to Dulag, Lelyte, where we beached and Army troops carried additional provisions aboard. The morning of 12 December 1944 saw 200 Army troops board LCI 982 and we were soon underway to join a huge convoy which majestically sailed through Surigao Strait, so bitterly contested only days before , and on out into the Mindinao Sea/ Destination: invasion of Mindoro.

The purpose of this operation was to split the Philippines in two and to provide dry weather airfields to support future large scale landings on Luzon. Intelligence warned that there would be around 1,000 enemy planes available to resist the invasion force and this sent a chill through every man aboard. We had learned all too well what the Kamikaze could do. As we neared our destination, gunfire was constant in the distance. On 13 December, off the coast of Negros, the cruiser Nashville was hit by a Kamikaze and was forced to return to Lelyte with more than 100 casualties.

The LSTs were the slowest vessels in the convoy which was underway at five or six knots. The radio was continually alive with shouts of “Move up Dumbo! Move up Dick tracy! Move up Jack the Ripper!”

D-Day was on the morning of 15 December. LCI rocket ships were the first to go in and plaster the beaches with their deadly fire. The LCI(L)s followed with their Army Troops. We were able to provide the troops with a dry beach and as we backed off, the LSTs began their approach. As soon as they hit the beach, hell seemed to erupt. Some 15 Kamikazes arrived overhead and attempted to bomb and crash the ships. Flak covered the sky over the beach but two of the LSTs were hit as we withdrew and approached our rendezvous area for our return trip to Leyte.

Our convoy arrived back in Leyte two days later on the 17th, the trip being blissfully uneventful. Since we were still subject to suicide raids, we resumed our “smoking” role. Enemy planes continued their bombings of Tacloban airfield and ships anchored in the Gulf.

The Kamikazes were one thing, but the ships and men in Lelyte Gulf were quite unprepared to cope with the typhoon which his us one day later on the 18th. Heavy rains combined with 120 mph gale force winds caused several Liberty ships to break their moorings and drift aimlessly about. We were rammed at least six times. We later learned that three destroyers were sunk in the storm with a loss of 790 men. Subsequently we experienced two lesser typhoons but managed to “hide out” in San Juanico Strait. We entered a floating dry-dock and received much needed repairs and, afterwards, began making preparations for the next invasion.

LCI 982 took aboard a contingent of 6th Army Rangers led by Colonel Henry Mucci. The Colonel, Captain Prince and Dr. Fisher shared my quarters. These were the troops that initially occupied the three islands at the entrance to Leyte Gulf some three days before D-Day and so were battle hardened veterans.

Two large convoys met near Surigao Strait on 4 January 1945 and proceeded into the Mindinao Sea. This huge convoy was made up of 850 ships with plenty of heavy support. The goal was the invasion of Lingayen Gulf in northeastern Luzon.

We proceeded northward along the coast of Mindoro and right under the noses of the Jap forces around Manila. Off Manila Bay, we watched our boys sink a Jap destroyer in night action. A huge ball of fire signified her finish. We went through several air raids as the convoy pressed northward along the Luzon coast. The carrier Omany Bay was sunk and several other ships hit thanks to the persistent Kamikaze raids.

As our convoy entered Lingayen Gulf and prepared for beaching, the invasion forces received the following message:

To the officers and men of the Sixth Division and active on the eave of our landing – I salute the best outfit in the U.S. Army with confidence that you will do a good job.

Best of Luck,

General Patrick

When it came time for them to go ashore, the Rangers had to disembark from our ship via “Ducks” because of the terrific surf. The landing were made on 9 January 1945 with more than 200,000 troops of the 1st and 14th Army Corps eventually being put ashore. Later, we found out that the Rangers proceeded south from Lingayen Gulf and after a long and cleverly planned march, were able to capture the prison camp of Cambanatvan and release hundreds of Allied prisoners. Dr. Fisher was killed on this mission. We took pride in being selected to carry these crack troops to battle.

[ A movie was made of the prison camp raid]

As usual, our duties after the landings consisted of laying smoke screens for the bigger fighting ships. We also had to stand armed guard at night for Jap suicide boats. Kamikaze raids continued but at a diminished rate. It was a sight to behold when the battleship California opened up with her formidable AA (Anti-Aircraft) guns during one of the Kamikaze raids during which we happened to standing off nearby.

During February we made two trips from Lingayen to Subic Bay hauling miscellaneous cargo back and forth. We were finally ordered to Manila Bay where we arrive on 1 March 1945, but were ordered to turn about and head back to Subic before making landfall. On 7 March we again left Subic, this time with orders to pick up a contingent of Army troops on Corregidor. As we entered Manila Bay, we could see hulks of several ships that had been sunk. Our planes were still bombing Caballo, a small island off Corregidor. On the morning of 8 March, the 982 beached on Corregidor and 200 tired officers and men came aboard. Corregidor had been reconquered.

I went ashore for a few minutes and saw some of the Jap suicide boats we had been warned to watch out for. Most of the crude little speedboats were hidden in caves around the island. Close inspection of the boats I saw revealed that they were powered by Chevrolet engines, undoubtedly removed from vehicles captured in Manila during the Japanese takeover four years earlier. As we backed off the beach, the skipper headed the 982 for Mindoro where we deposited the troops on 9 March. After laying over in Mindoro for a few days, we left for Leyte Gulf, arriving 16 March 1945.

Enemy activity had subsided in the Leyte Gulf area. Pockets of resistance were still active in Luzon and Mindinao, but things were clearly winding down in the Philippines. We had been through some 70 air raids and had seen countless Japanese planes go down.

During the next five months we were involved in more missions to various islands in the Philippines. Replacement troops had to be transported and we were available for duty in case an emergency arose. The first of these trips was to Zamboanga where the natives dive for coins. We were allowed to visit the Moro section called “Little Frisco” and unhappily noted that many buildings had been destroyed by bombing and fighting.

Three trips were made to the island of Samar. Visits were made to Catbalogan, the capital City, Llorente on the east coast and Guiwan which had been developed into a naval air base. While in Leyte Gulf, we were also used to transport Filipino guerrillas and acted as a hotel ship to disburse replacement Naval personnel. Shortly before the war ended we received orders to proceed to the United States for conversion to an LCI(R) rocket ship, obviously in anticipation of the invasion of the Japanese mainland, an operation that would result in hundreds of thousands of American casualties. But before we could get underway, the Japanese surrender was announced with a resulting sight that none of us will ever forget. Several hundred ships opened up with horns, search lights, whistles, bells and guns. The pyrotechnic display that ensued would dwarf any 4th of July show ever put on stateside. Radio silence went out the window.

The formal surrender by the Japanese took place on 2, September, 1945. Ironically, on 5 September, our flotilla of 36 ships, received orders to depart for Okinawa.

W had lasting memories of our 10-month ordeal in the Philippines. The 982 had participated in all the major invasions. We had lost three of our sister ships in Lelyte Gulf and witnessed many air raids and bombings. However, we also had many human interest experiences in our associations with the Filipino people and were never devoid of typical nautical humor. Certainly some of our ship’s complement wouldn’t forget the one-legged whore in Iloilo, Panay, or the Moros diving for coins in Zamboanga, Mindanao.

The war was over, but the travels of LCI-982, continued. We were issued foul weather gear and set sail on 5 September, where the BB New Jersey lay at anchor. A few of us went ashore and visited the capital city of Naha and the adjoining town of Shuri, which were both totally destroyed. We walked by several small shrines and monuments. Many archways, called Torii, led the way to Shinto temples.

The hillsides were embedded with ancestral tombs that the Okinawans used to care for their dead.

President Fillmore, in 1852, sent an expedition of warships to Japan to negotiate a treaty which would set up diplomatic relations and open the way for commerce between the two countries. Commodore J. C. Perry headed the expedition. One of his ports-of-call was to Okinawa, where he paid his respects to the Emperor at the summer castle of Shuri. In 1945, this historic castle lay in ruins.

During the 82 day battle on Okinawa, the Americans suffered nearly 7,000 men killed and more than 29,000 wounded.

On 14 September, 1945, twelve LCI’s received orders to get underway for the occupation of Shanghai, China. One day out of Okinawa, a terrific typhoon hit us. Decks buckled under our feet, masts were blown down, huge waves and violent winds tossed us around like a cork, a few men got seasick and flashed their hash. Our Group Commander received constant navigational and weather instructions as to various courses to sail to avoid the apex of the storm. Three days later, the storm subsided. The “Pitchin’ Bitch” survived another ordeal. Many mines had broken loose and floated aimlessly about off the Chinese coast. Near the north of the Yangtez River, we rendezvoused with the cruiser USS Nashville and the British cruiser, HMS Belfast. The first orders received applied to the uniform of the day and “Short Arm” inspection. We had been a part of the Dungaree Navy for a year and a half. The Nashville, followed by the Belfast and twelve LCI’s proceeded up the Yangtze River in column formation, turned into the Hwang Po River to the great Port of Shanghai. Personnel on all ships stood at attention and lined the rail. Meanwhile, thousands of Chinese along the river were cheering, waving flags and shooting off fire crackers.

On 19 September, 1945, the Nashville occupied the No.1 berth off the “Bund,” which, in the eyes of the Chinese, was recognition of the major sea power in the world. The British had occupied the No.1 berth for many years. The twelve LCI’s moored along the docks farther down the river. These ships constituted the Task Force that initially occupied the Yangtze River Delta and the Port of Shanghai, China.

The International Settlement was principally populated by the French, British, White Russians from World War One and thousands of Jewish escapees from Nazism.

Hundreds of Chinese children roamed the streets begging for food and money. Many Chinese beggars with various diseases and afflictions crawled on the streets. The water, sanitation and transportation systems had not been fully restored. The great Port of Shanghai, of around five million people, suffered during the Japanese occupation.

Our sole occupation of Shanghai ceased after two weeks. Additional Allied Navy ships arrived. Army Air Force units flew in from India and Burma. Then, Chinese Nationalist troops marched in.

Our stay in Shanghai was interrupted by more orders. 10 October, 1945 our Task Force set sail for Ningpo, a port city south of Shanghai. We sailed up the Yung River, past the city of Chinhai, and moored along the docks of Ningpo, on 13 October, 1945. We went ashore and ran into a French Catholic Bishop who had already been in China for 40 years. After visiting his church, he took us for a tour of Ningpo, which included a Chinese temple. We were the only Occidentals other that the Clergy in this city of 250,000 people.

The next day, we took aboard several hundred Nationalist troops. The Chinese troops couldn’t speak English. Communications were most difficult, including our instructions of how to use the ”Head.”

The Task Force left Ningpo on 15 October, 1945, and joined a larger Task Force already underway. This combined force had 10,000 Chinese troops aboard, and were bound for the Port of Kiirun Ko, Formosa (now Keelung, Taiwan). While underway, all ships received a radio message as follows:

“On reaching safety at Formosa, I wish to represent all the officers and men of our army to express with my heartfelt thanks for your help. In addition to that, I also hope to greet you and your men to have good health in future. At last, I wish the national relationship between America and China would be friendly forever in order to keep the world in permanent peace.”

Sincerely yours,

General K.T. Chen

The Task Force made the initial landing of Chinese occupation forces at Kiirun Ko, Formosa on 17 October, 1945.

Many sunken ships were in the harbor, with their masts, bows and sterns sticking out of the water. LCIs and LSTs moored along the docks that were lined with damaged warehouses. Every building in the city had been bombed. Our B24s had left their calling cards. The next day, hundreds of Formosans walked along the docks and provided us with a ceremonial and welcoming parade. They featured a display of large quilted flags and strange sounding musical instruments. The Chinese troops disembarked from our ships and bivouacked in the warehouses. Rotation, by the point system, had already begun, so we had several new faces aboard. Unlike most LCIs we were fortunate in having a Chief Bosun aboard. DBM Smith was very instrumental in training our Deck Gang in all the facets of seamanship. After two weeks in Formosa, we returned to Shanghai.

On the Yangtze River, we saw a couple of captured Japanese gun-boats with American prize crews aboard.

Hotels, stores, restaurants, bars, etc., had reopened and were doing a flourishing business. The river was loaded with traffic. Red Chinese propaganda bulletins began appearing on the walls of buildings.

In early December, I finally received orders to go home. I hitched passage aboard the CVE Makin Island. Twelve hundred Army Air Force men were already aboard. We set sail on 10 December, 1945, bound for Seattle, Washington, with a stopover in Hawaii. A couple of months later, the travels of the LCI-982 continued from Shanghai to Stateside – but without me.